WW 13: Hidden histories

Andy Billman on our relationship with the built environment, and the oft-overlooked stories that surround us

After an extended hiatus (for context, see my last post), Wellwatching is back in its new form, dedicated to exploring the intersection of wellbeing and the built environment.

I’m happy to kick-off this new chapter with a conversation with Andy Billman, a London-based photographer with a curiosity for built environments and the spaces we find ourselves in. With an appreciation for composition and arrangement, his images explore the interaction between constructed forms and our surroundings, inviting a closer reading of our relationship with the environment that often goes overlooked.

Last summer saw the debut of his first solo exhibition, Daylight Robbery, which explores the phenomenon of bricked-up windows of London, some that were remnants of England’s window tax. I loved the exhibit for its simple but powerfully thought-provoking look at a relatively unknown slice of British public health history. It offered an at-once timely and timeless reminder of nature’s fundamental importance to our wellbeing.

As we stretch into year three of pandemic living, and as the discipline of wellbeing architecture continues to grow, Andy’s work felt like the perfect topic with which to restart. Have a read below.

Tell me a bit about yourself: How did you get started in photography? Why did you choose to focus on the built environment?

I’ve always had an interest in photography. I did an art school foundation course, but ended up studying business at university.

After graduating, I went into advertising – but I never lost sight of my interest in photography. It was my cousin who finally persuaded me to take the leap to pursue photography further during Christmas holidays in 2019. In January 2020, I decided that by the following Christmas I would have made the leap. And here I am.

Now, I’m fully immersed in photography that tells stories in the context of the built environment. It's interesting to capture the stories of people in relation to their space, especially topics and narratives that would otherwise be overlooked and give them a moment to rise to the surface. They might be things that don’t mean much in isolation when people walk by, but you can create something really special and meaningful with the right composition and arrangement. You can show people what they might be missing.

Your photography exhibition, Daylight Robbery, in part references England’s ‘window tax’. What does that term refer to?

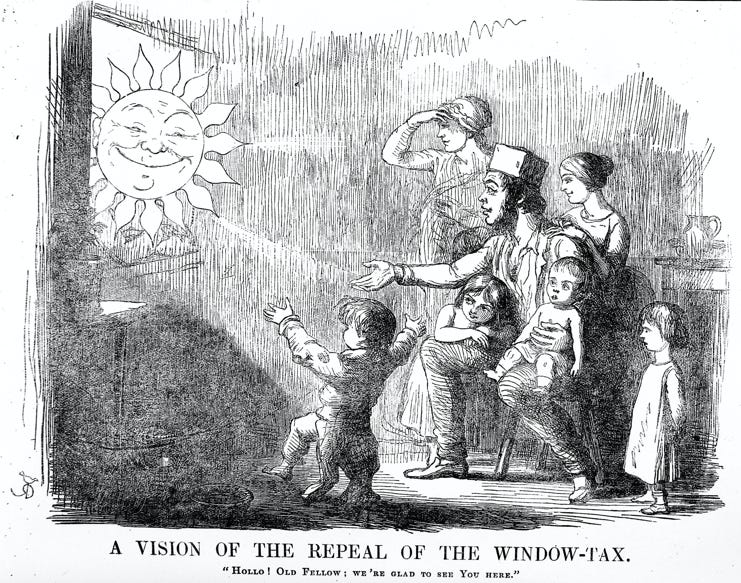

The tax, originally introduced in England in 1696 by William III, taxed people based on the number of windows featured in their homes. This was before any sort of income tax was introduced, and so the government decided that the easiest way to solicit income from households was to use windows as a proxy measure of wealth. Households with more windows were assumed to have greater wealth, and therefore were taxed at a higher rate.

What sparked your interest in it?

Walking around London, I started to notice that there were quite a few bricked-up windows in otherwise gorgeous homes – which at first look is quite strange. If you look carefully, there are lots of indents – some subtle, some less so – in walls that would have otherwise been windows.

I loved that these offered a natural framing: in a literal sense, with lines and structure and arrangement; but also metaphorically, bringing attention to a significant but lesser known story about the history of these neighbourhoods.

I wanted to find the stories behind these bricked-up windows – and that’s how I discovered that some were in response to the tax.

What happened as a result of the tax?

As you might have guessed, people didn’t want to pay more tax, and so they started boarding and bricking up their windows. So as a financial initiative, the tax failed to generate revenue for the government.

More importantly though, it had disastrous unintended consequences for public health. Essentially it became a tax on light and air. Without regular access to both, there were reports that it was causing ill health. And when your economy relies on healthy, productive people, you quickly realise that you’re shooting yourself in the foot by creating a significant barrier to the country’s wellbeing.

I was amazed at how much critique the tax received at the time, most notably from Charles Dickens. In 1850 he eloquently argued for the public’s right to nature, saying,

"Neither air nor light have been free since the imposition of the window tax. We are obliged to pay for what nature lavishly supplies to all, at so much per window per year, and the poor who cannot afford the expense are stunted in two of the most urgent necessities of life."

Source: The Wellcome Collection

What lessons do you think the window tax can offer us today?

The windowless walls of this era were almost like holding up a mirror for what we’ve experienced throughout the pandemic. Being limited to outdoor exercise only once a day and limited to the walls of our own home, I felt that it was certainly a good moment to resurface this slice of history.

These spaces offer a visually compelling reminder of the intuitive, but often ignored, knowledge that we need regular, consistent access to nature to thrive. And we need to ensure that the spaces we spend time in, whether for work or play, can help us achieve that.

I wanted people to sit with the tension between the well-composed beauty of these bricked-up windows, and the dark stories that are held within them. With my series, I hope that I’ve been able to resurface something that’s incredibly important but not often discussed.

What other aspects of the built environment interest you?

In its simplest form, I’m interested in the traces we leave in our surroundings and what they tell us about humankind’s relationship with the environment. Sometimes man-made structures are in harmony with our surroundings, sometimes not. I document overlooked subject matter objectively, and leave it to the viewer to decide.

What does wellbeing mean to you?

I’m a big believer in releasing, rather than suppressing, my thoughts and feelings. Letting my emotions flow, good or bad, has always been a strength of mine. And during the pandemic, I’ve certainly experienced how conversations with a friend can relieve long-held weights and release you from your own heaviness. Talking to friends and family, writing it down, exercising - however you choose to do it, anything that allows you to release and flow is important. It helps you be true to yourself.

What's been your biggest wellbeing breakthrough over the last year?

Mine has been an evolving and growing realisation, rather than a recent breakthrough or a singular moment, of learning not to be tied to a job. I’m very aware that my ability to evolve personally and professionally beyond and away from my old career is an incredible privilege, and I’m grateful to have reached this point.

What’s the next challenge that you’d love to take on?

I’ve recently returned from a month-long trip in Argentina. Being half-Argentine, I wanted to begin painting a picture through photography of the country I was experiencing. My next challenge is to explore how I can release a selection of the images for the wider public to engage with it.

Learn more about Andy’s Daylight Robbery exhibit here with prints available to purchase. He is currently sending the proceeds of one of his prints to the Ukrainian humanitarian crisis. For more information, visit his Instagram.