WW 06: Compassion by design

Oliver Farshi on Buddhism, holistic design, and facilitating better outcomes

Hello! After a mid-summer hiatus, Wellwatching is back. If you’re new, thanks for joining in - you can read previous interviews here.

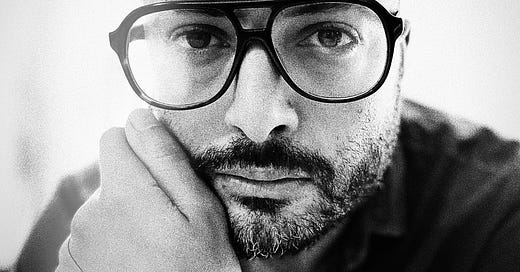

To get back into the swing of things, I’m thrilled to share my chat with Oliver Farshi, a British designer based in Brooklyn, New York who is the Head of Design at Kiva. Oliver designs things that reduce suffering and promote peace, health, and wellbeing. He’s launched projects with the likes of Google, LEGO, and Nokia, and has also collaborated with various NGOs including IRC, UNICEF, and War Child. He loves to make things: civic things for nonprofits, cloud-based things for developing countries, thoughtful things for museums, useful things for communities in crisis.

Olly offered a unique perspective on wellbeing that’s rooted in his years of meditation work, wide-ranging design experience, and Buddhist studies. We discussed the role of holistic design in facilitating better wellbeing outcomes, the risk of decoupling and commodification in the industry, and the Buddhist reminder that ultimately, we’re all in this together.

Have a read below:

Tell me a bit about yourself: What do you do?

I'm a designer. I design things that reduce suffering human suffering, and promote peace, health and wellbeing.

For example, I’ve developed a tool that helps humanitarian first responders communicate with refugees; a platform that gets critical information out to people in disaster scenarios; and designed the experience to t help people move through a major longitudinal clinical health study, or that help clinicians do lab work more effectively.

They’re all quite different, but the throughline is that there is some suffering occurring at some point in that situation, and the work I'm doing hopefully begins to reduce it – either systemically in the long-term, or acutely in the immediate-term.

How do you define what type of designer you are?

I don't, actually. There are, of course, different sub-disciplines within design. There are some areas that I don’t touch – for example, interior design – and others, like industrial design, that I’ve been exposed to but haven’t specialised in.

This sometimes gets contentious in the design community, but I don’t think it’s helpful to put up guardrails as to what sort of design I do or don’t do. Sometimes I’m designing a product or a visual experience. At other times, there is nothing to see – it’s more about how you feel, what you learn, and what you can do as you move through an experience.

Ultimately, I see design as a way of facilitating and moving through a problem, and helping other stakeholders – like engineers, strategists, product managers, policy makers, first responders – to create the right conditions and outputs to improve a process or outcome.

How did you arrive at your approach of ‘design to reduce suffering’?

A few years ago I was living in New Orleans, where I ran a design studio focused on civics. We worked a lot with the city as well as city-focused nonprofits. When a hurricane came through, we were told to evacuate but many in my community chose not to. During this time, many households across Greater New Orleans lost power for about five days.

The power outage was in many ways more destructive than the hurricane itself. The problem wasn't simply that we were all sitting in the dark, but that we didn’t know what was going on. No one had any information. Our mobile phones were dying. The real problem became, ‘I want information, and so does my community.’

Coming out of that experience, I wanted to figure out how I could alleviate this issue in future. My breakthrough moment was realising that even in a power outage, landlines still work because they're on a separate power grid. And so I figured out a way to make critical information available via an old-fashioned landline call: people could pick up the phone, dial a local number and an automated system would tell you where to find rations, shelter, and local updates.

Google heard about it a few years later, and asked me to lead their Crisis Response team that addressed these sorts of problems on a national and global scale. Rather than it being a typical growth-focused tech opportunity, its sole aim was to save lives.

Working on these initiatives resonated with me, and so I decided to make them my focus going forward.

What experiences have defined your understanding of wellbeing?

My introduction to meditation nearly a decade ago was really the main catalyst. At that point, I had lived with depression and anxiety for many years, and I was attempting to mitigate my symptoms in various ways.

When I finally gave meditation a try, it changed my relationship with depression and anxiety almost overnight. My tipping point was when I went on a retreat and was introduced to the idea of compassion in the context of meditation. You have to nurture it within yourself before you put it out there for others.

Since then, I’ve studied Soto Zen Buddhism, in which practitioners seek to fully experience every moment in the here and now. While I don’t identify as Buddhist, I’m very intentional about my daily practice. I find Zen practice so integral to my own sense of wellbeing as well as a collective sense of wellbeing, as its teachings are rooted in the idea that we're all connected.

What do you think is wrong with the way business and culture currently approach wellness and wellbeing?

While there is still a way to go, I think that culturally, wellness is increasingly proactive and nuanced in the way it’s communicated at scale – we're building a wider vocabulary around it that includes, for example, honest feelings, the mind-body connection, and a proactive approach to medicine and health. If these things make it more palatable and accessible to more people, I support that.

That said, the two main issues I see are decoupling and commodification. Many wellness practices are rooted in deep knowledge from different communities that, in some cases, are being superficially appropriated and assigned a value as a commodity.

With regards to decoupling, in the rush to democratise physical and mental health concepts more widely (and profit off of them), the industry has extracted and discarded the most important question of our collective existence, which is: why do we want to be well? We’ve seen this with, for example, yoga as an exercise offering in traditional gyms. Rather than asking questions or taking a reflective, investigative stance, we’re often encouraged to simply move through the movements. I suspect that we can’t just use a sanitised version of something that's so deeply profound and expect to get the sort of same emotional or spiritual payback.

Similarly, the industry continues to commodify – and charge for – long-held practices that were designed to be accessible, equitable, available in the first place. When I think about mental health apps specifically, I find that there’s an inherent conflict of interest. Once you start charging, you want to continue charging and keep the customer engaged. You’re then dealing with repeat engagement, where the aim of fostering wellness directly clashes with the desire to continue making money. I do think that these services are created by people who want more people to be well, but in practice I think the economics of them inevitably create a mismatch of values to business opportunity and interests.

These trends perpetuate the cultural and financial gatekeeping associated with wellness.

How do you see the design community evolving to cater to people’s overall wellbeing? What are the trends that you’re most interested in at the moment?

There’s an exciting shift in the design community whereby we as designers have a broader understanding of what design is and how it might be applied beyond pixel pushing, as a mix of service design, experience design, strategic design, et cetera. Being able to think more holistically about designers’ problem-solving abilities feels more appropriate when you want to go beyond the brief of, ‘I need to design an app that makes people feel better in X way,’ and take a more holistic approach for a more thoughtful output.

As part of this, the growing discussion around equity, inclusion, diversity is leading to a better understanding that more accessible and equitable design isn’t just important, but is inherently superior to what is only available to a few. To achieve it, we’re slowly moving towards cultures that are less dominated by white cisgender heterosexual males – and therefore, where approaches to and executions of design for aren’t solely created by and relevant for these particular men. When we design better, we can serve more diverse audiences, and vice versa. We can build these experiences that really work, and are fulfilling, meaningful and effective for more people.

We already know what the consequences are without this approach. Loopholes in tech privacy policies have led to accidentally outed students, and victims exposed to their abusers. This is the very real danger of having members of a team look and think like everyone else, who aren’t considering problems and needs from different perspectives.

What's been your biggest wellbeing breakthrough over the last year?

After working on my mental wellbeing for quite some time, I’ve started to think more holistically with my body in mind as well. And so, alongside a meditation practice, I’ve developed a regular exercise routine. Looking after the body is really just as much about looking after your mind, and so it felt right to prioritise it. I’ve thought more about what ‘eating well’ means to me too – it’s not simply about prioritizing ‘pure’ or ‘healthy’ foods, but eating with intention. If I want to eat junk food, I will – I’ll make an active and present choice to do so.

What does ‘wellbeing’ mean to you?

Acting with intent and compassion in how we care for ourselves and each other.

You can find out more about Oliver and his work here.